a bookclique pick by Jessica Flaxman

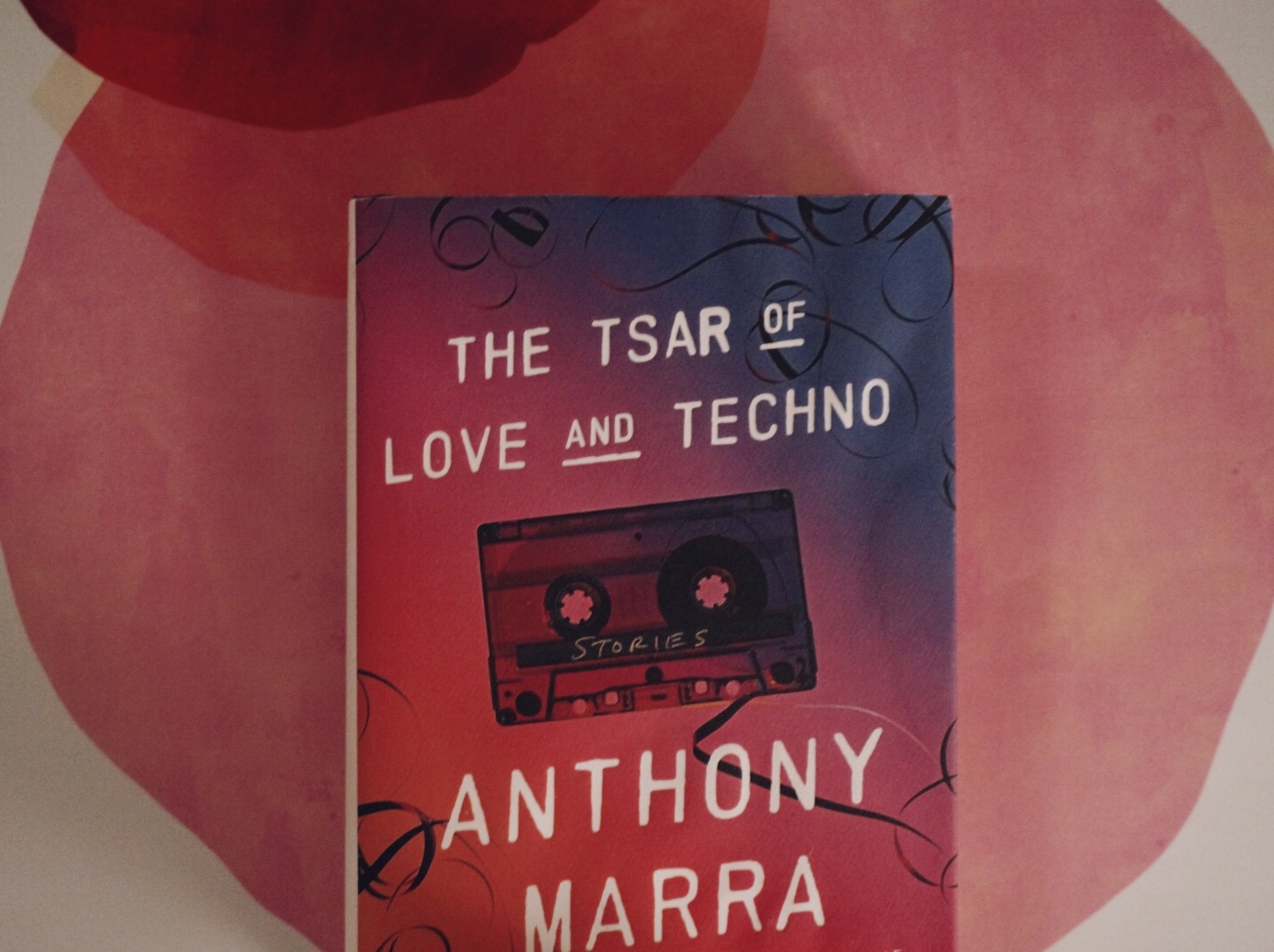

The Tsar of Love and Techno is an admittedly opaque title for a collection of interconnected short stories about Stalinist Russia, the USSR, and the modern conflict in Chechnya. But don’t let that put you off. Marra is a brilliant storyteller who brings characters and places to life like no other.

The Tsar in the book’s title is a figment rather than a person. Readers shouldn’t look for him, even in the story by the same name featuring Alexei, a young man who lives to go to dance clubs and get lost in the music. Alexei is no more the Tsar than his older brother, Kolya, a sensitive thug who is captured in Chechnya and spends his days planting seeds in a heavily mined hillside that once was the inspiration for a famous painting by the Chechen painter, Pyyotr Zakharov-Chechenets. Neither is the painter, nor the correction artist who adds a picture of a Communist party boss to the painting.

Marra’s stories are affecting tales of individuals whose seemingly small acts nonetheless have lasting impact. For example, Roman Markin is a government censor who erases enemies of the state from photographs and paintings in WWII-era Leningrad. A skilled painter, he is excellent at his job of removing people from the historical record. In their place, he secretly adds images of his brother, who believed in heaven and was convicted of religious radicalism and later executed. Markin stages another small rebellion when he erases all but the hand of a ballerina deemed an enemy and slated for historical oblivion. Many years later, Nadya, a restoration artist and scholar, writes articles about Markin without ever knowing his name, cataloguing his handiwork left in ample evidence despite his own disappearance.

In this interwoven plot, Marra makes a powerful argument that legacy is indelible despite the fact that names and faces may be forgotten. Each story has its own depth of detail and its own devastating revelation while also connecting with the other stories. My favorite is probably “Granddaughters,” told from the collective perspective of a group of six girls who grow up in Kirovsk, a heavily polluted city in Siberia where Kolya and many other characters originate. These girls manage their jealousy of Galina, the pretty one who wins a rigged Miss Siberia Beauty Pageant, and their grief and acceptance when friend number seven, Lydia, is murdered for being a snitch. The women speak in one voice, powerfully summarizing the victory in their intentionally underwhelming parenting in an area of the world where individualism has often resulted in punishment: “We’ve given [our children] all we can, but our greatest gift has been to imprint upon them our own ordinariness. They may begrudge us, may think us unambitious and narrow-minded, but someday they will realize that what makes them unremarkable is what keeps them alive.”

Without a doubt, this is a kind of love. In fact the whole book is inflected with deeply moving love stories. Love for a woman who has been scarred and blinded in a bombing. Love for a nephew without a father. Love for a brother who wanted to be an astronaut but turned out to be a murderer. Love for a painting that is plain but poignant. Love for a story that a fellow prisoner of war tells over and over again, a story that was always assumed to be true but was always a fiction. Like Marra’s incredible book.